University and community officials are working to honor the life of the father of African American history.

University and community officials are working to honor the life of the father of African American history.

“If a race has no history, if it has no worthwhile tradition, it becomes a negligible factor in the thought of the world, and it stands in danger of being exterminated,” wrote Dr. Carter G. Woodson in the The Story of the Negro Retold in 1935.

Woodson is most known as the father of black history; he was one of the first scholars to study African American history.

Many recognize February as Black History Month but few know of Woodson’s influence on black history.

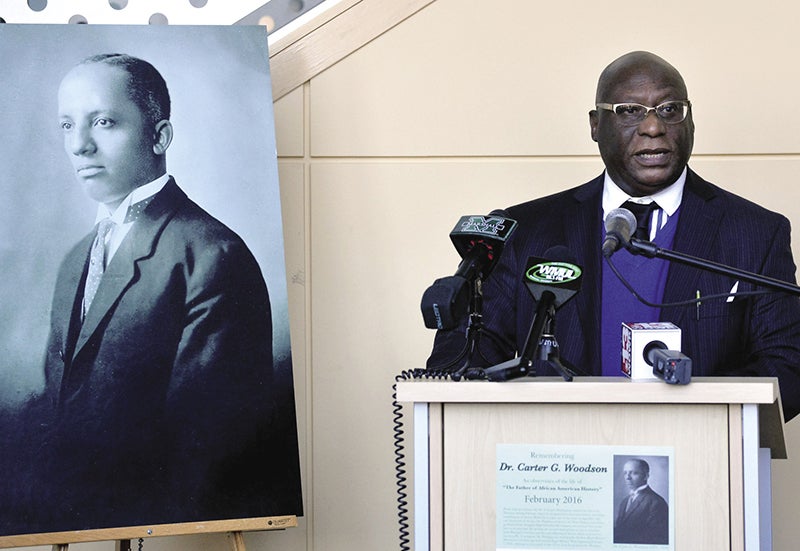

Burnis Morris, Carter G. Woodson Professor of Journalism and Mass Communications at Marshall, said Woodson did not believe in black history, but he believed in all history. He wanted all races, not just blacks, to know blacks had made contributions in history. He also believed if whites were aware African Americans had a great past there would be less discrimination.

“You can argue that the period we are in now is very similar to the period Woodson was in when he began promoting black history,” Morris said. “Few people believed blacks had a history worth recognizing. Illiteracy was very high and fewer people read books. Think about today, fewer people read books, so we need to interest people again in reading and learning about the past in order to prevent the mistakes of the past.”

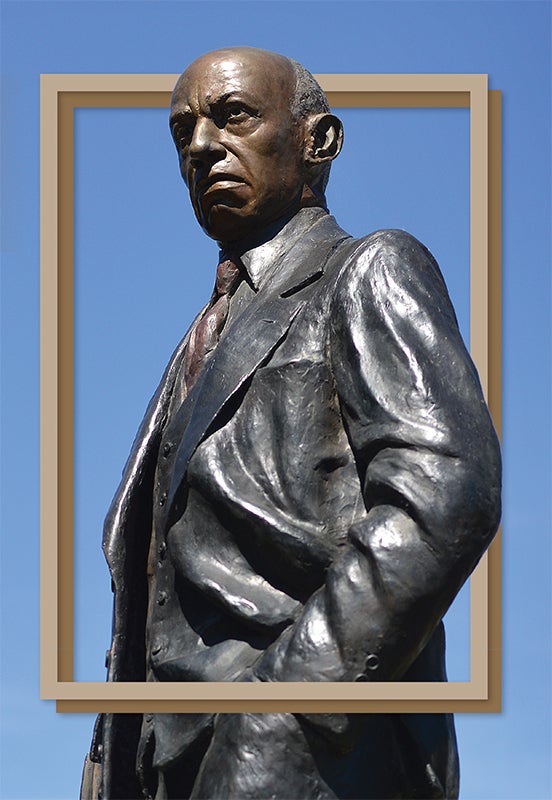

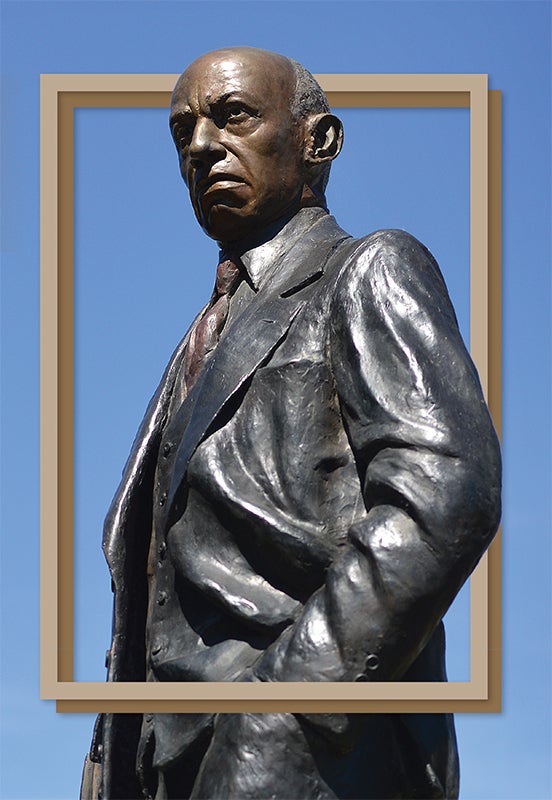

The statue of Carter G. Woodson on Hal Greer Boulevard has been there for more than 20 years but few people know his inspiring story.

Woodson was born in Buckingham County, Virginia, in 1875, the son of former slaves. Like many African Americans of their time, his family came to West Virginia to begin new lives working in the booming coal mining and railroad industries. The family moved to Huntington when Woodson was in his teens, and his father was a carpenter and helped build the town, including construction of the C&O Rail Depot on Seventh Avenue.

Carter G. Woodson worked in coal mines in Fayette County, West Virginia, with his father and brother to financially support the family. During this time, Woodson was only able to devote a few months each year to his education.

Carter G. Woodson worked in coal mines in Fayette County, West Virginia, with his father and brother to financially support the family. During this time, Woodson was only able to devote a few months each year to his education.

While working in the West Virginia mines, Woodson listened to the stories of the everyday lives of fellow black miners and was inspired to document and teach the struggles and contributions of the African American people.

Woodson began his studies at Huntington’s Douglass School in 1895 and completed his high school education there in about a year.

He then studied literature at Berea College, and he returned to Fayette County as a teacher before coming back to Huntington to become principal at Douglass High School in 1900. Douglass High School was located across Hal Greer Boulevard from where Woodson’s statue stands today.

Woodson went on to serve as dean of both West Virginia State University and Howard University. While dean at West Virginia State, he wrote the history of blacks in education in West Virginia. He documented the first black schools in each county.

Carter G. Woodson’s career in education as teacher and student eventually led him around the world from the Philippines to France and Africa. Woodson received an A.B. and A.M. from the University of Chicago in 1908, and his doctorate in 1912 from Harvard University, becoming the first person of former enslaved parents to earn a doctorate in history.

“You can argue that during his time in West Virginia, he learned some things about education and about running a black history program en route to becoming the father of black history,” Morris said.

“You can argue that during his time in West Virginia, he learned some things about education and about running a black history program en route to becoming the father of black history,” Morris said.

Woodson founded the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History in 1915, which began the modern Black History Movement, and in 1926 he inaugurated Negro History Week, which evolved into the present-day celebration of Black History Month every February.

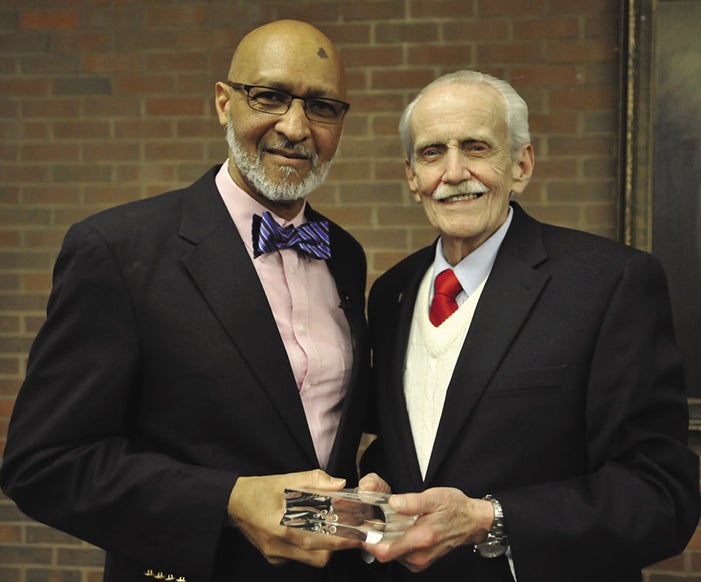

Marshall University’s John Deaver Drinko Academy and Dr. Alan Gould, its executive director, continue to honor Woodson by observing his life and legacy and his ties to the Huntington community. Huntington Mayor Steve Williams proclaimed February 5, 2016, Dr. Carter G. Woodson Day. Resolutions were passed in the West Virginia House of Delegates and Senate. Sen. Bob Plymale, D-Cabell, and Del. Sean Hornbuckle, D-Cabell, were in attendance to talk about the significance of Woodson’s ties to West Virginia. A representative from Sen. Joe Manchin’s office submitted a statement in the Congressional Record.

“So few people know Woodson’s story,” Morris said. “If they knew his story, he would be an inspiration to them and that is what’s motivating Alan Gould. Alan has been trying to get the community interested in Woodson for 30 years.”

Other examples of how Woodson is being remembered include the Marshall University Society of Black Scholars’ creation of the Carter G. Woodson Distinguished Student Awards, which was presented to seven students in April. This was the second year for the event that began in 2014 as a Service Learning project and is now an annual event.

“One of the reasons so many of these awards and activities are taking place is because the university is attempting to elevate the importance of Carter G. Woodson’s contributions throughout the future,” said Maurice Cooley, associate vice president of Intercultural Affairs. “We felt as a university and as a community, we needed to come together to recognize his contributions.”

“One of the reasons so many of these awards and activities are taking place is because the university is attempting to elevate the importance of Carter G. Woodson’s contributions throughout the future,” said Maurice Cooley, associate vice president of Intercultural Affairs. “We felt as a university and as a community, we needed to come together to recognize his contributions.”

Cooley said it was the students’ decision to name the event after Woodson and to honor students that have the same characteristics as Woodson. Characteristics of award recipients include striving toward excellence in achievements, contributing to the lives of others, contributing to the intercultural balance of society, serving others and using their knowledge to raise the knowledge of others.

Woodson believed that in order for black Americans to move forward, they had to recoup history.

Woodson wrote in The Mis-Education of the Negro, “History shows, then, that as a result of these unusual forces in the education of the Negro he easily learns to follow the line of least resistance rather than battle against odds for what real history has shown to be the right course.”

Cooley said it is vitally important for students to understand that where they are today originates from the contributions and the work of others who came before them.

“Life was not always like it is here today and there is still much work to do in our society,” Cooley said. “While there has been substantial progress and it has not come together on its own, some of it came about because of the work, the deeds and the contributions of specific people. Everybody must know that for the sake of us making future contributions.”

Sandy York is an assistant professor in the W. Page Pitt School of Journalism and Mass Communications. She lives in Ashland with her husband and 8-year-old daughter.

Photos: (Top) This statue of Carter G. Woodson stands on Hal Greer Boulevard in Huntington. (Second from top) Burnis Morris, Dr. Carter G. Woodson Professor of Journalism and Mass Communications at MU and a Drinko Fellow, speaks at the opening ceremony for the month-long observance Dr. Carter G. Woodson’s life and work. (Third from top) Bishop Samuel H. Moore (left), who gave the inaugural Dr. Carter G. Woodson Lecture at Marshall, receives a memento of the occasion from Dr. Alan Gould, executive director of the John Deaver Drinko Academy. (Below) Dr. David Trowbridge explains the Clio app at one of the Woodson events. Users of Clio can get information on their digital devices about places and events in history that have taken place in their location.

University and community officials are working to honor the life of the father of African American history.

University and community officials are working to honor the life of the father of African American history.