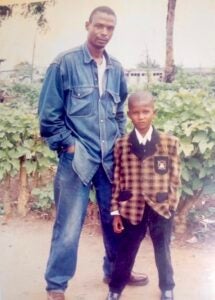

As a young boy in Nigeria, hauling water was Obinna’s first job. Countless gallons, every day, were hauled several hundred yards from the public fountain to his family’s house in Lagos.

“We didn’t have electricity or running water,” he said. “My Mom had a 40-gallon tank that needed to be filled up for her food business each day. I started by hauling a gallon or two to help my older sister. Eventually, I could do it myself, and I needed fewer trips as I grew stronger.

“I tell people that this is why my arms are so long – hauling all those heavy jerry cans of water as I was growing up.”

The only son among Anthony and Angela Anochili’s six children, Obinna grew up surrounded by his sisters, two older, and three younger. To make ends meet, Angela prepared and sold food.

“She was what people think of when they imagine young African women,” Obinna said. “She started by hawking food in the streets, with the food in a container balanced on her head, one baby strapped on her back and another on her front.”

Her food was good though, and soon became popular enough that she grew to have a stand on the street, where the bicycle taxi drivers brought their riders to her for lunch. Eventually, she started a catering business.

Life in Lagos was hard. Political corruption and economic instability led to difficult conditions. For Obinna, basketball became his escape.

“My friends and I would get up at 5 in the morning and jog to the gym and then work on ball handling,” he said. “Then we’d go back home and go to school. After school, I was in charge of washing the dishes and the pots for my mom’s business. When I got that done, I’d go back to the gym.”

At first, they’d watch the older players, patiently waiting their turn. Eventually, Obinna became one of the first players picked. They’d play until dark, then he’d haul water again for the next day’s cooking.

His abilities on the court soon drew the attention of prep school coaches from the United States. His family made the difficult decision that basketball in America was the best opportunity to give Obinna a better life. That led to 14-year-old Obinna boarding a plane for the first leg of a journey that was supposed to take him to Arizona.

“I’d never been on a plane before, and when we took off — we were flying to Abu Dhabi — I was panicking,” he said. “I was light-headed, and my stomach was dropping. I was sitting by a Nigerian who was going to England, and he got me to calm down.

“I told him that it was my first time on an airplane, and I was scared, and I didn’t even know how to get to my next plane. I begged him to help me when we got to the airport in Abu Dhabi.”

The stranger helped Obinna get through customs and then to the gate for his flight to New York, but the young traveler’s troubles were just beginning.

“I took the flight more than 12 hours to New York, but when I got there, it was so much more confusing than the airport in Abu Dhabi,” he said. “I borrowed a stranger’s phone to call my mom and told her I was scared and didn’t know what to do. We got it figured out to catch my next flight to Washington, D.C., but then it got even more complicated.”

“The prep school actually had gotten me a train ticket from D.C. to Arizona, and I didn’t know how to get from an airport to the train station. My mom told me to wait and she’d figure something out.”

His mother made a quick connection to a Nigerian student who was living with a family named the Killens in Chapmanville, West Virginia, which didn’t seem too far from Washington. They called the student, who told Doug and Tammy Killen about the youngster who’d soon be on his way to D.C. The family jumped in their car to go meet Obinna.

“They were waiting when I came out of the airport. It was November, and I just had a light shirt because it had been warm in Lagos. I was shivering,” Obinna said. “They say that as soon as I got in the car, I was knocked out. I was completely exhausted, both mentally and physically, jet lagged and scared. I was out.”

“Later, they took me to my first restaurant, a Cracker Barrel. What I remember is drinking cup after cup of hot chocolate like it was water.”

“They took me back to their home in Chapmanville, and after a couple of days there, I called my mom and told her I didn’t want to go on to Arizona, where I didn’t know anybody, that I wanted to stay with the Killens.”

“They took me in. Eventually, they adopted me, and I spent my high school time in Chapmanville.”

Obinna was now Anochili-Killen, and his basketball game developed the way his family hoped it would in America. Before long, he was being recruited by schools like Cincinnati, Penn State, West Virginia and others. He was even invited to play in the prestigious Peach Jam event in Atlanta, which is where Coach Corny Jackson, then a Marshall assistant, made a big impression with a small act of kindness.

“It was huge,” Obinna said. “The best players and the best coaches — Coach Cal, Coach K, everybody. And I was really struggling at the start.

“I was frustrated. We were at a break, and Coach Corny just told me to relax and go play, that I’d be just fine. And I was. I played much better from then on. That stuck with me that he was with me when it wasn’t going well. I remembered that moment.”

Traveling on the AAU circuit was more than just an opportunity for Obinna to improve his game. When playing in tournaments, he’d save his food money to send back to help pay for his sisters’ school needs.

Traveling on the AAU circuit was more than just an opportunity for Obinna to improve his game. When playing in tournaments, he’d save his food money to send back to help pay for his sisters’ school needs.

“Some places had food for the teams, but we’d also get money to go eat,” he said. “If I could get enough to eat without spending that money, that’s what I did.

“I’d save it up from our events all summer and then send it to my family. With the currency exchange rates, what doesn’t seem like that much money here is a lot more in Nigeria. Then when I got to Marshall, we get our “town checks” to cover our expenses — but I’ve saved all I can from that to send back to my sisters. They need it more than I do.”

The journey to college basketball took one more major detour. Through the recruiting process, Obinna decided to go to the University of Cincinnati and play for Coach John Brannen — a Marshall alumnus and Herd Hall of Famer.

He took a recruiting visit to Marshall just because it included a football game between the Herd and Bearcats at Edwards Stadium. Marshall lost the game, but gained a future Sun Belt Conference Defensive Player of the Year as Obinna was won over by two more Marshall alums.

“Coach Corny took me around campus and I liked the school and the team,” he said. “Then they showed me how Coach (Dan) D’Antoni developed his big men.

“I was known as a defensive player, but I saw how other Marshall big guys like Ajdin Penava, Iran Bennett, and Jannson Williams were taught and encouraged to handle and shoot the ball on the perimeter and how their offensive games improved.”

Obinna had found his new home and family. A family that became even more important as both of his parents passed away.

“Coach Corny gave me a flower when my mom passed. I still have it at my house. It’s beautiful.”

His families, both in Nigeria and West Virginia, weigh prominently in his decisions. A career that saw him score 1,682 points (No. 14 all-time at Marshall), haul in 781 rebounds (No. 9), and shatter the old Marshall record with 287 blocked shots meant the transfer portal and NIL deals were there for the taking.

“I’m a loyal guy, to my family, to my team, to my school,” he said. “I’m there for the people who have been there for me.

“I know how good it is here. When I started playing basketball in Lagos, I was shooting at rusty, bent, nine-foot rims and rusty backboards right on the wall with a concrete court. Now I’ve spent my career at Marshall with everything I need, things people in other places don’t even dream about. I still appreciate it when I turn on a hot shower.”

He also admires the Marshall supporters, those fans who’ve cheered him on in the Cam Henderson Center.

“The thing I’ll always remember about Marshall fans is that season when we went 13-20, but we sold out the Henderson Center five times,” he said. “That’s the kind of loyalty that Marshall fans show the basketball team, and that’s what I appreciate. We go other places, and the fans aren’t there if that team is losing. Our fans show up when it’s bad, not only when it’s good.”

He also values his Marshall accounting degree.

“I’ve had awesome professors at Marshall, my entire time here,” he said. “Playing basketball while in school is a lot during the season. We travel and miss class for two or three days or more.

“The professors work with us to make sure we can keep up. They’ve been understanding. They’re the reason I’ve had such a great career at Marshall academically as well as in basketball.”

Rather than chasing some quick money in the short term, Anochili-Killen took a wide-angle look at his future. He hopes to make money playing professional basketball. He has workouts scheduled with NBA teams in the coming weeks, but his ultimate plan is to put his education to work back in Lagos.

“As a country, Nigeria has a lot of oil,” he said. “It could be a rich country. But in the past the leadership was bad and they had corruption. Now it’s getting much better.”

He may have arrived in West Virginia as a weary, young traveler, unsure of what would come next, but Obinna Anochili-Killen leaves Marshall as a star, on the court, in the classroom, and in the lives of everyone lucky enough to know his story.

Armed with his degree in accounting, Obinna has plans for a future in real estate back home in Lagos.

“Lagos is an awesome place – a big city (the population is more than 20 million) – and you have the beaches. I’d like to develop resort areas and tourism there,” he added.

He also has a deep loyalty to the people and places who believed in him. Someday, he hopes his sisters and even his own children will come to Marshall.

“I’d like for there to be Anochilis on this campus for a long time to come. Hopefully, they’ll be playing in the green and white.”